I served for 15 years in multiple capacities at the Foundation, after pitching and landing work as a producer and project manager on the digital remix of 77 Million Paintings by Brian Eno.

At Long Now…

…I served as fellow, copywriter and blogger for 15 years, New Media Director for 3 years, and as Interim Advancement Director for one year. I built the Foundation’s social media presence from scratch, including writing a majority of the copy for all social posts on Facebook, Twitter and Linkedin from 2007-2011, while also hosting a membership-only live blog during Seminars.

But what is Long Now?

As New Media Director, I initiated and scaled our global community and social media presence around our projects, and initiated a strategy for meetups with the CEO of Meetup.com. We moved from several dozen members in 1 city, to over 2,000 members in 20 cities and 8 countries in Europe, Asia, Australia and North and South America.

Here is a TEDx talk on my work at Long Now, which I designed and delivered.

Donor Jeff Bezos outlines the project and concepts behind the Clock of the Long Now.

Board member Brian Eno tells the story of the original inspiration for creating Long Now: a trip to New York City on hiatus from his music career.

While serving as Interim Director of Advancement, I was tasked with initiating the Fund of the Long Now, a long-term investment vehicle for the Foundation.

I wrote the copy for this introductory three-minute speech and fundraising pitch by Long Now executive director Alexander Rose. I also wrote and selected all copy for the Fund of the Long Now campaign, below. This included emails, blog posts, gift instructions, speeches, public talks and quote selections.

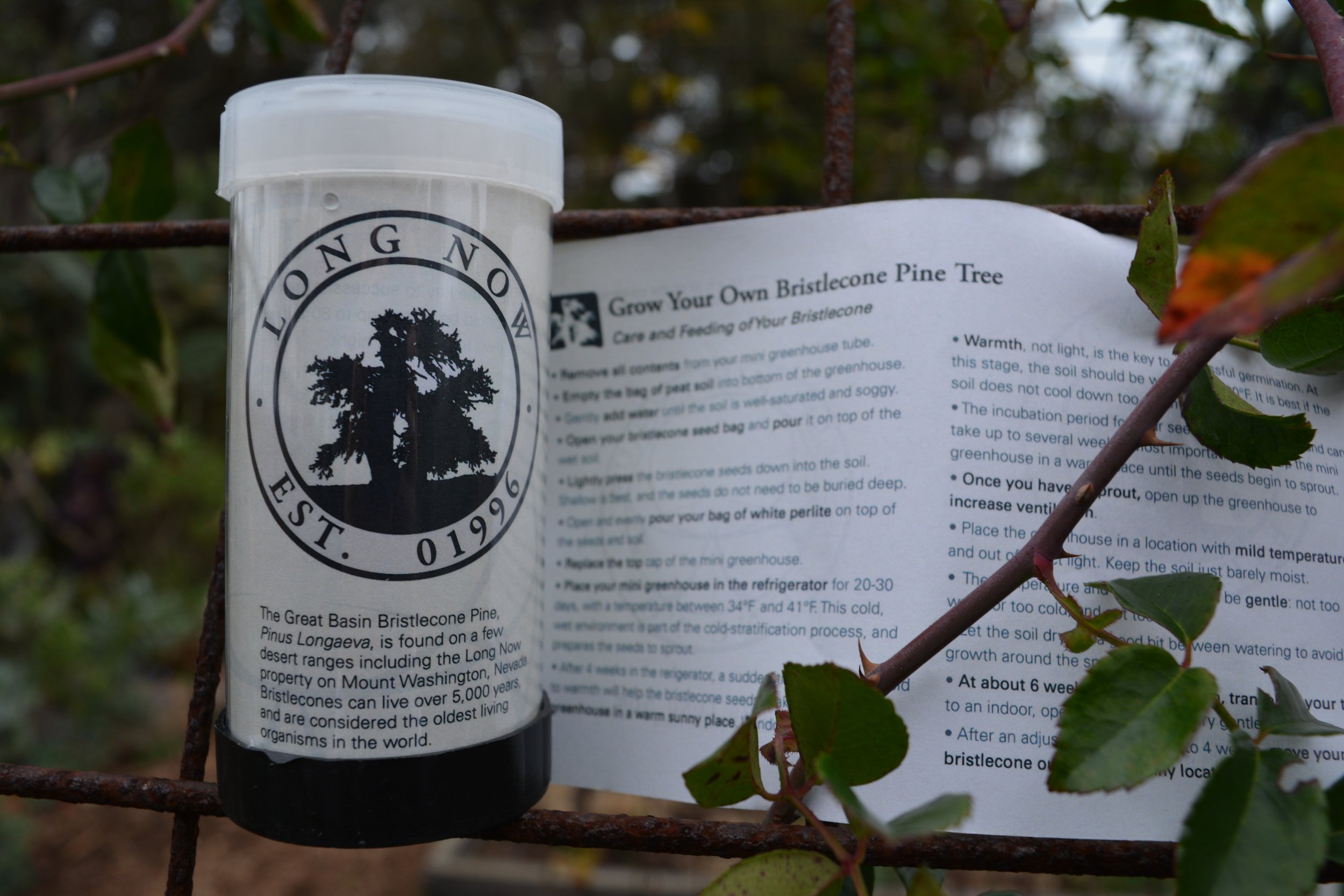

This blog post was written as a promotion for the Foundation’s annual fundraising campaign. Beyond this post, I also wrote and edited the copy and instructions for planting the bristlecone pine tree kit [shown in the above image] while overseeing the creative team which designed, packaged and shipped the kits.

Growing a forest of 5000 year trees

by Bryan Campen

This year, your contributions to The Long Now Foundation support the creation of the Fund of the Long Now. We will leverage this fund, through centuries of interest and investments, to help make Long Now a truly long-term institution.

Supporters of the fund also receive a limited edition Bristlecone Pine Tree Kit (pictured above) in honor of their substantive contribution. Our goal is to send kits to as many donors as possible, but there are only a limited number. Bristlecone pine trees are considered the oldest living organisms in the world, known to last up to 5,000 years, and are a living symbol of our commitment to ensuring Long Now extends into the deep future.

We are happy to report that as of this morning, we’ve shipped more than 180 Bristlecone Kits to our supporters. To those who have contributed, thank you.

We need to reach $500,000 in order to put this fund into active management, and to generate good returns to support our activities and programming.

There is still time to join this year’s group of visionary donors in creating a truly long-term future through Long Now.

I built the Long Now social media presence starting in 2007, until 2011. We moved from less than 5,000 followers, to more than 40,000 in a 3 year period.

Flesh and blood long-term library

by Bryan Campen

Great piece in the Washington Post on the future of ancient books in Timbuktu.

“A sort of ancient-book fever has gripped Timbuktu in recent years” as outsiders encounter large, family-owned collections of ancient manuscripts which remain in private hands. at the same time, Timbuktu’s residents “hope to lure the world to a place known as the end of the Earth by establishing libraries for visitors to see their centuries-old collections of manuscripts.” For those who do not sell their collections privately, small libraries are in bloom across the city.

Yet with instructions from ancestors to preserve ancient books within families, there is a reluctance to place them in libraries currently being built for the very same purpose. “Many owners refuse to part with their books… but they struggle to raise funds to restore or display them.”

It is interesting that that so many families were able to preserve these manuscripts for so long. What caused this culture of long term preservation?

Consider the Library of Alexandria, which Stewart Brand covers in Clock of the Long Now. It experienced at least four fires, two from “collateral damage” by Ptolemy VIII (88 B.C.E) and Julius Caesar (47 B.C.E.), and two from religions on the rise (Christianity and Islam).

The ability to preserve these books over many centuries so far rests with families intent on honoring and adhering to requests from ancestors, a rather small and fragile model compared to the infrastructure needed to build a great library. Yet it is possible that a family with instructions from ancestors is, in some sense, a better library than a library itself.

Six hundred years ago, Timbuktu was packed with university students (at about 25,000, the size of a modestly large mid-western university these days) and a constant flow of merchants. It was a nexus of trade and intellectual life on the continent which then slowed. Perhaps because it did not intersect with the dramatic tension between three continents, like Alexandria, it was less prone both to collateral damage *and* the request by military or religious leaders to dispose of books not relevant to the prevailing winds. In any case, this slowing may well have ensured greater preservation over time.

It’s also confirmation that a library in the middle of a continent–away from the intersection of countries, military conquests and ascendant religious movements–is a really good idea. With “ancient-book fever” now in Timbuktu, some combination of library and family models will have to preserve them.

The Fund of the Long Now

by Bryan Campen

June 02016 marks Long Now’s twentieth anniversary. In terms of a new nonprofit, it is a pretty good run. But for Long Now it means that we still have at least 9,980 years left to go…

So we decided to build a fund to better ensure our future, and at the same moment put deep time in your hands. We have created The Fund of the Long Now, a donor fund that we will invest in to help make Long Now a truly long-term institution.

As a thank you to those who provide tangible support to The Fund, we have made a limited edition set of Bristlecone Pine Tree Kits. These kits will be sent to everyone who can make a substantive donation.

The bristlecone is one of the longest living species on earth, and a living symbol of our shared commitment to the deep future, whether we measure that in centuries or millennia.

The Fund of the Long Now is being built to back up our promise to that future, and to support the operating budget of a truly long-term cultural institution.

Once we reach $500,000, The Fund of the Long Now will go into active management that is specifically designed around long-term thinking. We have been testing the principles of the fund with our financial advisors for several years, and will continue to tune it as we move forward.

The idea behind the Fund originates from one of our core principles, to leverage longevity, and was best illustrated in Stewart Brand’s The Clock of the Long Now. So as you consider making a contribution we leave you with his quote:

The slow stuff is the serious stuff, but it is invisible to us quick learners. Our senses and our thinking habits are tuned to what is sudden, and oblivious to anything gradual. Between the near-impossible win of a lottery and the certain win of earning compound interest, we choose the lottery because it is sudden. The difference between fast news and slow nonnews is what makes gambling addictive. Winning is an event that we notice and base our behavior on, while the relentless losing, losing, losing is a nonevent, inspiring no particular behavior, and so we miss the real event, which is that to gamble is to lose.

What happens fast is illusion, what happens slow is reality. The job of the long view is to penetrate illusion.

One Billion years of memory

by Bryan Campen

Last week Kurzweilai.net ran a clip of this post from Nanowerk (a more complete report will be available here June 10th):

“A new experimental computer memory device that can store 1 terabyte per square inch… with an estimated lifetime of more than one billion years has been developed by Alex Zettl of UC Berkeley and colleagues.”

This is possible through a series of lab tests and theoretical studies that show the device has “temperature stability in excess of one billion years,” an estimate that appears to be the maximum thermal read on the life of the device.

The first thought I had on reading this, aside from Douglas Adams’s “Deep Thought” (the computer that takes several million years to solve the riddle to life, the universe and everything), were the words of Jeff Rothenberg: “Digital documents last forever—or five years, whichever comes first.” Even several decades is an accomplishment. The article itself gives a nod to the virtues of paper by way of William the Conqueror’s Domesday Book, a model of data preservation. The Domesday Book has lasted 900 years compared to its digital counterpart, recently expired at twenty.

But this puts a lot of interesting questions to the issue of the digital dark age: how would we carry out the task of movage, porting data from one medium to the next as new systems appear? And how to avoid the billion-year legacy system from hell?

It also says a lot about us. Like the old joke about inflation in Austin Powers, the numbers in which we traffic have spiked over the past half century. Where one million used to do the trick, one billion commands attention and is now much more attractive. The range of numbers we tend to see as audacious but imaginable–though we have a hard time grasping them at all–are in the billions and now low trillions. This is the language of hard drives, moguls, world population and public debt. It is a language already on our minds.

Now if only someone would frame this billion year storage claim as a long bet.

Like the old inflation joke in Austin Powers, the numbers in which we traffic have spiked the past several decades.